Artelier Interview: Janine Lambers on the Ancient Craft of Gilding & her Artistic Journey

- david

- Sep 28, 2022

- 9 min read

As international art consultants, Artelier specialises in curating art for luxury residential, hospitality, yacht and aviation projects. Artelier's feature wall collection – Artist Walls – presents a collection of artists whose originality of ideas and dedication to their materials makes them true contemporary masters. Through collaborating with Artelier, they have created large-scale custom art commissions that reinvent the concept of the mural for the modern age, pushing the possibilities for feature wall art.

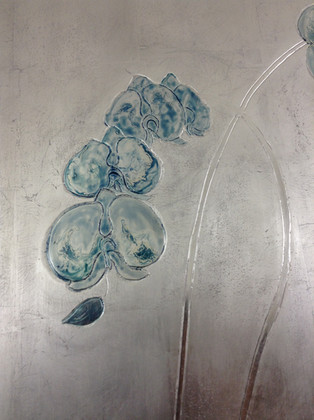

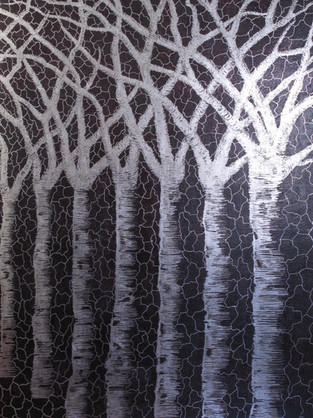

Having honed her skills in the craft of gilding, Janine Lambers began to experiment with creatively expressing the beauty and transience of nature with the highly specialist techniques she had mastered. Lambers has a deep understanding for her materials, enabling her to create dazzling effects with gold, silver and platinum leaf which utilise their unique qualities. In this interview, Lambers discusses her own artistic journey and her approach to her work, as well as providing an illuminating look into the breadth of ancient gold leaf practices.

Could you discuss your training, and what inspired you to begin your artistic journey?

I trained to become a gilder and conservator in the mid-nineties by way of a traditional 3 year apprenticeship at Anton Roetger GmbH in Germany. In Germany, it’s structured so that you attend the Masters school once you have gained professional experience after your apprenticeship, but I moved straight to New York; in any case, though, you are considered a master after 10,000 hours of work. In Germany, the Masters always have an exhibition, and some of what they present is also more experimental. While I was in Germany I attended an exhibition of this kind, where I saw a few works that completely inspired me. Something just opened up at that moment, and I thought to myself: "Wow, there are other opportunities, other possibilities to apply this craft".

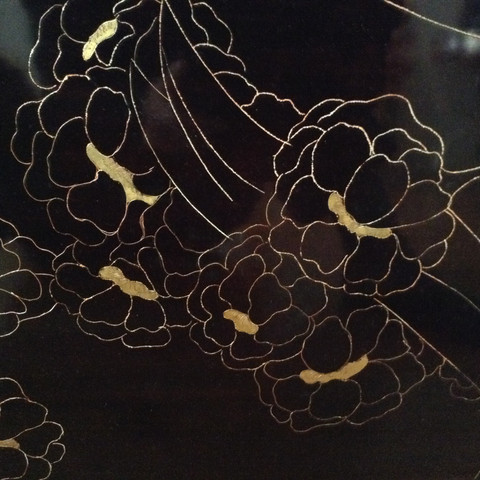

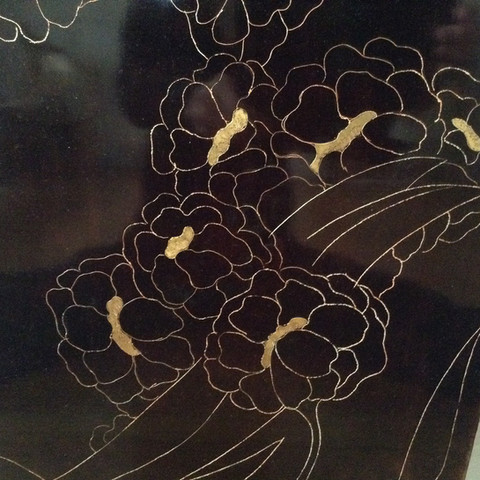

After I relocated to NYC, NY, I worked at Lowy Frame and Restoring Company, one of the most prestigious antique frame businesses in NYC. Entering their workshop was like walking into a frame museum – they had over 4,000 antique frames, original frames from the 15th century through til today. The company not only handled frames, but were also restorers or conservators of works on canvas and paper. So, I was also exposed to really high-end art there, such as Picasso's and Degas'. During that time, I also came across art screens and room dividers, by the likes of Charles Prendergast, Jean Dunand and Max Kuehne. That to me was just the beginning of thinking about room dividers; one of the first artworks I made was a screen with poppies, in 2008. That piece was acquired by an art dealer, who had a big gallery in New York city – that was the beginning.

After 5 years at the Frame restoring company, I started my own business and have been fortunate to work with many great craftspeople, including Miguel Saco at Miguel Saco Fine Furniture and Restoration Inc., art dealers, galleries, auction houses, designers and clients in NYC, Greenwich, CT and surrounding areas. They all helped me to further develop my understanding of my craft. This business is still my occupation, however, I also artistically experiment with the centuries-old gilding techniques that I have honed over the years to create new concepts in 2 and 3 dimensional art works. In training, I am a craftsperson through and through, but with a strong artistic inclination and intuition.

What is the technical process of gilding? Could you explain the terminology and materials?

There are various different gilding techniques, of which the most precious is called water gilding. Generally this is done on a wood substrate. In order to cover up the grain of the wood, several layers of gesso – an animal glue and chalk mixture – are applied, and sanded to a smooth surface. Afterwards, two to three layers of clay or bole (earth pigment bound in animal glue) are added, which are the binding foundation for the gold leaf to adhere to.

Once this has dried, the glue is reactivated by what is known as "gilder's liquor", a water and alcohol mix. This “liquor” is brushed onto the surface, and the gold leaf is then laid onto this wet surface in a swift motion. Upon drying, the leaf can be burnished with an agate stone to achieve its characteristic deep glow. This forms the base of gilding, but in addition other techniques to manipulate the gold leaf can be added to create different effects.

What do you find intriguing about your medium and what drew you to it?

Gold leaf for me has the qualities of beauty, luminosity and mystery . Beauty because it adds depth to shapes. Luminosity because it enlightens everything it touches. Mystery because it changes continuously with the changing light throughout day and night. Gold leaf also changes depending on its purity. The more precious metals are alloyed with non-precious metals, which can create varying degrees of oxidation, and produce very intriguing effects.

Currently I have started to work with more details of form. Nature starts to look more like we perceive it. Having said that, certain abstract versions also come up and are waiting to be expressed. I follow my instincts in what wants to be expressed. Most of my works are concepts that I eventually plan to expand into groups of works, but since I started I have found that so many ideas bubble up that I have mostly created unique, single pieces rather than groups of works.

"Nature starts to look more like we perceive it" is an intriguing concept – could you expand on that idea of perception in the context of your work?

I meditate a lot, and the meditation practice that I do is Vipassana. Vipassana is about seeing reality for what it is, and the basic sense is that, in a way, we live in an illusion. One of the things we do in this apparent reality is that we try to hold on to concepts or ideas by way of identifying. I've read a lot of books regarding how what the eye sees is actually not the way it is before being transported into the brain – the brain is actually what sees things. This is not a reaction we do consciously, the brain filters it for us from the moment that we see something. Many of the things that we see are therefore not the way they truly are.

I think that sense can be applied to a lot of abstract art. I'm not saying that looking at abstract art is closer to reality, but it's certainly not further away from reality. We may look at something that looks red or green, but there's a certain law of physics behind that which makes our body interpret it for us in that way. Ultimately, it might therefore not necessarily be the “truth”. That's why I say that the shapes we see take on more of a form depending on how we think we see reality.

You especially look to nature in your art. What qualities of nature inspire your work with gold leaf?

I live in a green area, up the Hudson valley in New York. We have the river here, and rolling green hills. I also grew up that way. I have lived on and off for about 10 years in the city, and it felt as though there was something missing in my life, so nature was a big part of why we chose to come and live here. With nature, it’s all about observation, seeing how it constantly changes. You observe how it buds in spring, is vibrant in summer, and ends up dying in winter. I go on walks every day, and I also have my garden which surrounds me with nature.

When you just perceive without thinking, you see nature differently, and all of those images stick with me. It makes a huge part of my art. One of the images I tackled fairly early on was trying to imitate that radiance of the sun. Observing change is also important to the practice itself, as for instance I work a lot with tarnishing silver, where changes in oxidation changes the material.

Are you interested in the ancient origins of gilding? Are there techniques from different cultures that have interested you?

I am very interested in the fact that the application techniques have not changed in centuries, which I find fascinating in a world where information seems to double all the time. There is something grounding in ancient knowledge and wisdom. I am a person who is very drawn to both nature and to history, and especially the gilding techniques of different countries.

For example, there is a Japanese technique called "urushi", using urushiol oil, although unfortunately we cannot use it as the process is not allowed anymore. It's toxic, and produces a highly allergic reaction. It's a technique that creates enormous sheen in gilding, and has been used for all the Japanese lacquer wares, for example. While I am interested in reading about many specialised ancient gilding techniques, I cannot use many of them as they often include materials such as urushiol, mercury and lead, which are not allowed anymore.

There's another ancient technique, which I haven't tried out yet, but which I would very much like to. The standard size of gold leaf is 8.5cm x 8.5cm, and it's very difficult to pick up the entire leaf without breaking it. To apply the gold leaf to panels, the traditional Chinese gilders created a rectangular funnel, which was exactly the size of the gold leaf, and put a thin layer of silk on top. They then inhaled on one end, attaching the gold leaf delicately to the silk, and gilded by blowing the leaf back onto the panel. I’m going to try to see if I find that effective for me! Nowadays we have a gilding brush, so I've never tried it out, but when I come across these other techniques I’m so tempted to try them.

What unusual gilding techniques have you worked with in your restoration work? How did it differ to your usual practice?

I worked on a gilded Ancient Egyptian sarcophagus, for instance. One of the main differences is the leaf thickness – the thickness of the leaf is usually 100x thicker than gold leaf is now. The standard today is 10mu, which is a tenth of a thousandth of a millimetre. It's phenomenally thin, you can really only pick it up with a brush, otherwise you'd break it. But back then, they used thick gold leaf in comparison.

Other than that, however, if you stick with the original work of the water gilding very little has changed, especially in the last 500 years. They are trying to imitate it with modern techniques, such as using acrylics, but the quality just doesn't come anywhere near the ancient techniques of using an animal glue, which range between hide glues to fish glues. These ancient techniques are fascinating.

Do you feel connected to a lineage of ancient gilders?

Yes, in a way! Gilding does slow down this very fast time that we're living in. These glues are not set recipes: you cannot just say 'x amount of clay or chalk' with 'x amount of glue' and then whisk it together. It really requires learning to understand the materials, because they are natural, they are organic. Therefore, they do not come out the same way every time. You can get one batch of an animal glue that is different from the next one, and if you don't know what the consistency of your gesso has to be, then you will run into trouble.

I think it is something you can only learn, truly learn, over time – when you're constantly working with these materials. You have to train yourself in the technique itself too, even just laying the leaf; it only comes with repeating the process over, and over, and over again until it becomes intuitive. I always say that in gilding, the slower you go, the faster you go. If you try to rush or hurry anything, it doesn't work and just backfires. If you actually take a step back and breathe, and then get into that meditative state of mind when you're gilding, then it flows. I think that approach should really tell us something, even in life.

When approached with a project brief for an artwork, how does the design evolve? Is there an idea that you’re developing at the moment?

Artelier contacted me recently with a concept for doing a ceiling installation onboard a BBJ Max. Upon seeing the drawing, I had an immediate vision of how we could achieve that idea. It was the same feeling as with the 5m Mt Fuji wall installation, which I recently delivered for Artelier onboard the yacht M/Y Aurora Borealis.

I began envisioning how I could layer a natural background using gold leaf, and manipulating it to create a rich tapestry of branches, flowers and a fading background. I find there is a slight difference between art that stands on its own as an art piece, and art that is integrated into the design and acts as decoration for a home, yacht or airplane. Integrated art needs to be subtle so as not to obstruct the overall composition of the room, yet also unique enough to accentuate this particular aspect of the room's design.

I do feel very inspired when creating work for a specific context, such as when it will be integrated into design. This possibly comes down to my experience of working with art frames. A frame can make or break a painting – it has to stand on its own, but it should not overpower the painting. In that sense, I approach something like a wall or a ceiling in the same way. These architectural features are for me a part of the concept of the room, and so the artworks have to accentuate them and bring out beautiful aspects.

Janine Lambers has collaborated with Artelier's art consultancy on numerous artwork commissions for interiors, and is included as part of our 'Artist Walls' collection – visit her dedicated page on our website here. The second half of her interview, about Lambers' inspiration, can be found here.

Artelier's art consultancy plays a fundamental role in all artwork commissions, and as the appointed art consultant for projects we bring artists and clients together to achieve forward-thinking and intelligently curated art installations. Discover more about our feature wall collection: Artist Walls.